Moʻolelo Monday

On the first Monday of the month a traditional or modern moʻolelo depicting the culture, values, language or traditions of Hawaiʻi, will be shared through a virtual platform. These mo‘olelo promote literacy within the classroom and home, and encourage ʻohana to read and learn together. Moʻolelo are shared by staff and guest storytellers.

MOʻOKALALEO

In the 1820’s, Kauikeaouli, Kamehameha III was the catalyst for the rise of literacy in Hawaiʻi. He stated, “ ʻO Koʻu Aupuni, he Aupuni palapala koʻu. My kingdom shall be a kingdom of literacy”. Within our moʻokalaleo, we share a literacy component that extends our moʻolelo journey.

Puʻu-Ke-ahi-a-kahoe

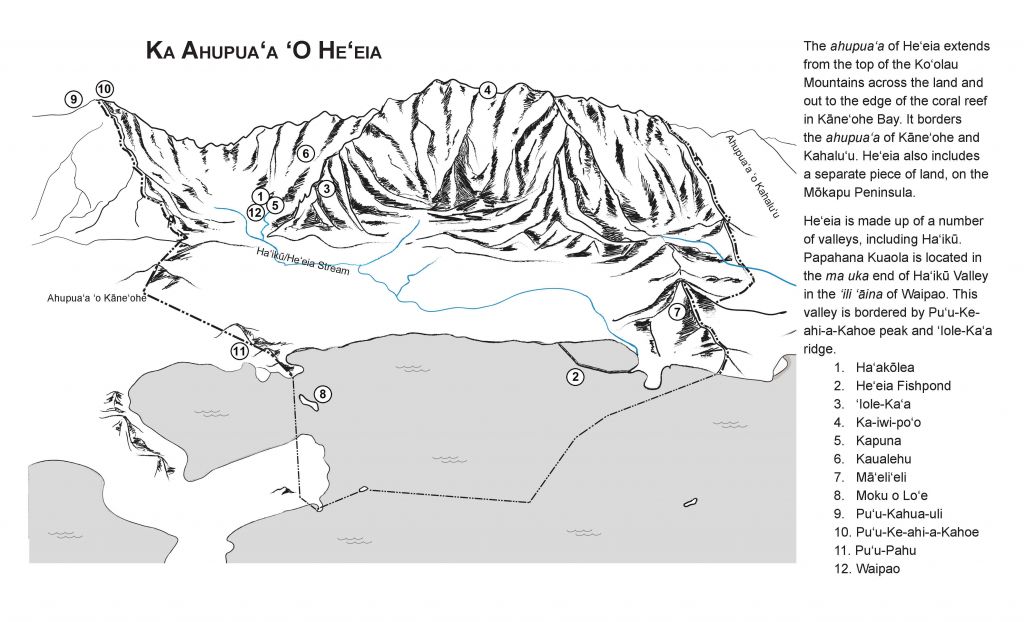

A few months later, a terrible famine came to the ʻāina. There was an extreme shortage of food and everyone was hungry. Some people would not share the little food they had. Since smoke from an imu meant food was cooking, it attracted many people to come for the food. Often times there was nothing left for the owner. Because smoke rising from an imu is more visible during the day, some people started cooking the limited food they had in the darkness of night. Sadly, many people had stopped practicing the Hawaiian value of sharing resources. Kahoe faced the same food shortages as everyone else. However, he had places to live in two ahupuaʻa: one in Kāneʻohe in front of Ke-aʻa-hala and one in Heʻeia near the pali in Haʻikū Valley. When it was time to cook, Kahoe travelled to his place in Haʻikū. Because of its location, the smoke from his imu was carried almost a mile away before it was visible at the top of the Koʻolau Mountains. It didnʻt matter if he cooked during the day or at night—no one knew when Kahoe was cooking until after he was done.

A few months later, a terrible famine came to the ʻāina. There was an extreme shortage of food and everyone was hungry. Some people would not share the little food they had. Since smoke from an imu meant food was cooking, it attracted many people to come for the food. Often times there was nothing left for the owner. Because smoke rising from an imu is more visible during the day, some people started cooking the limited food they had in the darkness of night. Sadly, many people had stopped practicing the Hawaiian value of sharing resources. Kahoe faced the same food shortages as everyone else. However, he had places to live in two ahupuaʻa: one in Kāneʻohe in front of Ke-aʻa-hala and one in Heʻeia near the pali in Haʻikū Valley. When it was time to cook, Kahoe travelled to his place in Haʻikū. Because of its location, the smoke from his imu was carried almost a mile away before it was visible at the top of the Koʻolau Mountains. It didnʻt matter if he cooked during the day or at night—no one knew when Kahoe was cooking until after he was done.

An old Hawaiian proverb says, “Ko ko a uka, ko ko a kai (Those of the uplands share their crops, those of the seaside share their catch).” That is what is considered an appropriate way of living. Should misfortune befall those living in the uplands, so too shall it fall shortly thereafter upon those living along the seaside––all will be affected.

An old Hawaiian proverb says, “Ko ko a uka, ko ko a kai (Those of the uplands share their crops, those of the seaside share their catch).” That is what is considered an appropriate way of living. Should misfortune befall those living in the uplands, so too shall it fall shortly thereafter upon those living along the seaside––all will be affected.Puʻu-Ke-ahi-a-kahoe

Ma ka welau o nā pali hāuliuli o nā Ko‘olau, ma ka ‘ao‘ao ko‘olau o O‘ahu, aia ka pu‘u ‘oi‘oi i ho‘oka‘awale ‘ia nā ahupua‘a ‘o He‘eia a me Kāne‘ohe. Ua kapa ‘ia ua pu‘u ‘oi‘oi nei ‘o Pu‘u Keahiakahoe. E ‘ike nō ‘oe i ia pu‘u ‘oi‘oi i kēia lā, e kū nei ma waho ala o ke kulanui kaiaulu ‘o Ko‘olau. He wahi mo‘olelo kēia e hō‘ike ‘ia ke kumu no ke kapa ‘ia ‘ana mai o nei pu‘u, ‘o Pu‘u Keahiakahoe.

He mau makahiki aku nei, aia kekahi ‘ohana, ‘ekolu keiki kāne a me ho‘okahi kaikamahine, i noho ai ma ka moku ‘o ‘Ewa ma O‘ahu. Hākākā mau nō kēia po‘e keiki me ko lākou mau mākua. Hō‘ihi ‘ole lākou a hilahila maoli nō ko lākou ‘ano. Ua kauoha ‘ia lākou, e ha‘alele iā ‘Ewa ma muli o ko lākou mau ‘ano hana hewa.

Ua ne‘e a noho lākou i ka moku ‘o Ko‘olaupoko ma ka ‘ao‘ao ko‘olau ma O‘ahu. He mau mahi ‘ai nā keiki kāne ‘elua, ‘o Kahuauli a me Kahoe ma ka ‘āina momona ‘o Kāne‘ohe a me ke ahupua‘a ‘ē a‘e ‘o He‘eia. ‘O ke keiki kāne hope, ‘o Pahu, he kanaka lawai‘a ‘o ia e noho ana ma kahakai ma He‘eia. ‘O Lo‘e, ke kaikamahine, ua noho ihola ‘o ia ma kekahi mokupuni li‘ili‘i ma ke kai kū‘ono ‘o Kāne‘ohe.

Ke kipa mai ‘o Pahu i kona mau palala i uka, e hā‘awi manawale‘a ‘o Kahoe i kāna poi ‘ono. Ua ho‘omākaukau ‘ia ka poi me ke kalo i mālama ‘ia e Kahoe. Akamai ‘o Pahu i ka lawai‘a ‘ana. He waiwai ka i‘a no ka po‘e Hawai‘i, no laila, waiwai nō ho‘i nā i‘a i mau ‘ia e Pahu. Akā na‘e, ma hope o ka pau ‘ana o ka lawai‘a e Pahu ma kahi o Kāne‘ohe Bay a i ‘ole ma ke kai hohonu, ua mālama ‘ia nā i‘a ‘ono loa nona iho a lawe ‘ia wale ka maunu koena i mea e ho‘ohālikelike me Kahoe. Li‘ili‘i nō nā i‘a maunu a ho‘ohana ‘ia kēia ‘ano i‘a i mea e lawai‘a ai i nā i‘a nui. ‘A‘ole pono ka hana a Pahu iā Kahoe. He hewa nō.

I kekahi lā, ua kipa mai ‘o Lo‘e iā Kahoe e ki‘i i nā kalo maiā ia. Ua ninau koke akula ‘o ia “Ua pau ke kālua ‘ia ‘ana o ka ulua ma ka imu?” Nānā wale ‘o Kahoe i kona kaikuahine. Pane akula ‘o ia, “‘A‘ohe a‘u ulua ma ko‘u imu. Ua hā‘awi mai ‘o Pahu ia‘u i ka i‘a maunu.” ‘A‘ole ka ulua he i‘a maunu, he i‘a nui a ‘ono nō ho‘i. “Akā na‘e, e ke kaikūnane,” i ‘ōlelo akula ‘o Lo‘e, “Ua loa‘a nā i‘a he nui iā Pahu i kēlā me kēia lā. ‘A‘ohe manawa i loa‘a ‘ole iā ia ka i‘a. ‘A‘ole paha ‘o ia e ho‘ohālikelike i kāna mau i‘a me ‘oe?” Hū a‘ela ka hoka a me ka huhū ‘o Kahoe. ‘A‘ole maopopo iā ia ka hana pī a Pahu me kona mau i‘a. Auē! Pī ‘ino lā ‘o Pahu a manawale‘a nō ‘o Kahoe. Ma hope o kēia hana, maopopo iā Pahu, ua ‘apo nō ‘o Kahoe i i ka hana kūpono ‘ole a Pahu iā ia.

I ka wā kahiko o ka Hawai‘i, ua ho‘ohālikelike nā kānaka a pau i ko lākou mau mea mai ka ‘āina a me ke kai me kēlā a me kēia kanaka. No ka po‘e Hawai‘i, ‘o ka ‘ohana nō ho‘i, hā‘awi manawale‘a i kā lākou mau mea me nā kānaka i noho ma ke ahupua‘a like. Ua ho‘ohālikelike pū me nā kānaka e noho ma ke ahupua‘a ‘oko‘a. He wahi kaiaulu kūka‘i ia i mea e loa‘a ai nā mea kūpono i nā kānaka a pau, e like me ka mea ‘ai.

A i kēia lā, ua kapa ‘ia kēia mau wahi o nei ‘āina ma muli o kēia mau kānaka ‘ehā.

- He wahi moku ma ke kai kū‘ono ‘o Kāne‘ohe i pili pū ‘ia me He‘eia a kapa ‘ia ‘o Moku o Lo‘e. ‘O Coconui Island kona inoa kapakapa.

- He wahi pu‘u ma kahi o ke kai i ho‘oka‘awale ‘ia ke ahupua‘a ‘o He‘eia a me Kāne‘ohe i kapa ‘ia ‘o Pu‘u Pahu.

- He ‘ili ‘āina ma Kāne‘ohe a me he pali welau o nā Ko‘olau i kapa ‘ia ‘o Kahuauli.

- He welau o nā Ko‘olau ma waena o nā ahupua‘a ‘o He‘eia a me Kāne‘ohe i kapa ‘ia ‘o Pu‘u Keahiakahoe.

No laila, ke noho ‘oe ma Ko‘olaupoko, e nānā kūpono ‘oe i kēia mau wahi i kapa ‘ia ‘o nā kānaka ‘ehā a ho‘omana‘o nō ho‘i i ko lākou mau mo‘olelo a me kā lākou hana pono.

He wahi ‘ōlelo no‘eau i ‘ōlelo ‘ia, “Ko ko a uka, ko ko a kai” (‘O nā kānaka ma uka e ho‘ohālikelike i ko lākou mea ‘ai, a ‘o ā kānaka ma kai e ho‘ohālikelike i ko lākou mea ‘ai). ‘O kēia hana ka hana kūpono o ke ola. Inā he mau pilikia kā nā kānaka o uka, he mau pilikia nō ho‘i kā nā kānaka o kai.

He wahi ‘ōlelo no‘eau i ‘ōlelo ‘ia, “Ko ko a uka, ko ko a kai” (‘O nā kānaka ma uka e ho‘ohālikelike i ko lākou mea ‘ai, a ‘o ā kānaka ma kai e ho‘ohālikelike i ko lākou mea ‘ai). ‘O kēia hana ka hana kūpono o ke ola. Inā he mau pilikia kā nā kānaka o uka, he mau pilikia nō ho‘i kā nā kānaka o kai.Moʻo ʻŌlelo

Weekly, a Mo‘o ‘Ōlelo, a succession of Hawaiian words or phrases will be shared. The mana‘o behind each word or phrase relates to the mo‘olelo being presented. This component will enhance cultural awareness and knowledge through Hawaiian language.

Famine, time of famine, destitution of food, impoverished In old times, famine was a common and well documented event. Although Hawai’i was home to an abundance of resources, times that were considered famine were usually times when kalo cultivation, once the staple of Hawai’i, became insufficient enough to provide for the community. The foundation of the Hawaiian diet was based on vegetables and complex carbohydrates. Kalo, ‘uala, and ‘ulu provided most of the calories while fish provided most of the protein.

Literally translating to “The fire of Kahoe”, Keahiakahoe is a cliff along the Ko’olaupoko mountains in the Kāne’ohe quadrangle. The peak, Pu’ukeahiakahoe, overlooks the valleys of Kamanaiki(Kalihi) and Kamananui(Moanalua). Keahiakahoe is named after the mo’olelo involving the protagonist, Kahoe, who strategically made the fires of his imu far upland.

‘Ōlelo No’eau #2699

Pua ka uahi o ko a uka, mana’o ke ola o ko a kai.

When the smoke from the fires of the upland dwellers rises, the shore dwellers think of life. Shore dwellers depended on the uplanders for poi.

An ʻŌlelo Noʻeau says in the moʻo ʻōlelo to “Ko ko a uka, ko ko a kai (Those of the uplands share their crops, those of the seaside share their catch).” That was ka nohona Hawaiʻi, the Hawaiian way of life, Hawaiian lifestyle. Should misfortune befall those living in the uplands, so too shall it fall shortly thereafter upon those living along the seaside, all will be affected.